Capítulo 4 - MÉTODO

DE INSPEÇÃO POR CORRENTES PARASITAS

traduzido do livro: AIR

FORCE TO 33B-1-1 / ARMY TM 1-1500-335-23 / NAVY (NAVAIR) 01-1A-16-1 -

Manual Técnico - Métodos de Inspeção Não Destrutiva, Teoria Básica

- GERAL

- Ponto de Balanço

- Parâmetros

- Frequência

- Ganho

- Ângulo de Fase

- Sensibilidade

- Filtros

- Análise de Modulação

- Resposta de Frequência

- Inspeção de Furos de Rebites

- Trincas na Parede dos Furos de Rebites

- Trincas de Fadiga

- Trincas de Corrosão Sob Tensão

- Acabamento Superficial e Dimensões de

Furos de Rebites

- Efeito de Borda

- Preparação do Furo de Rebite

- Aparelho de Inspeção de Furos de Rebites

- Varredura Manual

- Varredura Automática

- Dispositivo de Varredura Rotativo

- Sondas para Dispositivos de Varredura

Rotativo

- Ajustagem da Sonda

- Proteção da Sonda

- Compensação de Lift-off na Inspeção de

Furos de Rebite

- Padronização de Ajustes do Aparelho

- Velocidade e Trajetória da Varredura

- Alinhamento da Sonda

- Distância Sonda-Borda

- Interpretação do Sinal de Correntes

Parasitas na Inspeção de Furos de Rebite

- Furos Ovalizados

- Furos com Rebites Não Removíveis

- Aplicação de Inspeção dos Furos

- Espaçamento da Sonda ao Furo

- Guias de Varredura ao Redor de Rebites

Não Removíveis

- Seleção da Sonda

- Padrões de Calibração para Furos com

Rebites Não Removíveis

- Filetes e Cantos Arredondados

- Bordas (Incluindo Cantos Vivos e

Arredondados)

- Ocorrência de Trincas

- Requisitos da Aparelhagem para Ocorrência

de Filetes e Cantos Redondos)

- Padrões de Referência para Filetes

- Corrosão

- Requisitos do Sistema para Detecção de

Corrosão

- Tipos de Corrosão

- Ataque Uniforme

- Pites

- Ataque intergranular

- Esfoliação

- Trincas de Corrosão Sob Tensão

- Seleção da Frequência

- Seleção da Sonda

- Padrões de Referência para Corrosão

- Prodedimento de Inspeção para Detecção da

Corrosão

- Preparação da Peça a Ser Inspecionada

- Medição da Condutividade no Campo

- Condutividade das Ligas de Alumínio

- Efeitos do Tratamento Térmico na

Condutividade do Alumínio

- Discrepâncias em Tratamentos Térmicos de

Ligas de Alumínio

- Aplicação de Medição da Condutividade

- Separação de Ligas e Revenidos

- Medição de Condutividade e Materiais

Magnéticos

- Aplicação Típica

- Controle de Tratamento Térmico

- Determinação de Danos por Calor e Fogo

- Medição da Condutividade

- Aparelho para Materiais Magnéticos

- Efeitos das Variações das Propriedades dos

Materiais

- Condutividade

- Efeito de Borda

- Curvatura

- Material do Clad

- Permeabilidade Magnética

- Geometria

- Espessura do Metal

- Efeitos das Variações das Condições de

Ensaio

- Frequência

- Sondas para Medição da Condutividade

- Efeito Lift-off na Medição da

Condutividade

- Efeito da Temperatura nas Medições de

Condutividade

- Detecção de Descontinuidades

- Capacidade do Sistema de Ensaio

- Seleção da Sonda

- Tipos de Sonda

- Material

- Acessibilidade

- Requisitos de Frequência

- Relação Sinal-Ruído

- Relação Sinal-Ruído e Detectabilidade

- Influência da Frequência no Ruído

- Técnicas de Supressão

- Solucionando Energia

- Efeitos de Lift-off

- Fontes de Variação de Lift-off

- Supressão do Lift-off

- Métodos de Compensação de Lift-off

- Aparelhos de Análise no Plano de

Impedâncias

- Ajuste de Fase

- Efeito de Lift-off na Detectabilidade

- Compensação do Efeito de Lift-off na

Detectabilidade

- Defasagem Devido a Trincas

- Materiais Ferromagnéticos

- Descriminação de Fase

- Oscilação/Vibração da Sonda

- Efeitos da Localização da Trinca na

Detectabilidade

- Localização e Orientação das Trincas

- Trincas na Borda da Peça

- Inspeção das Bordas da Peça

- Dispositivos de Fixação e Suporte para

Inspeção de Bordas

- Curvatura

- Detecção de Descontinuidades Sub

superficiais

- Análise no Plano de Impedão de Trincas

Sub superficiais

- Detecção de Trincas Sob Revestimentos

Metálicos

- Efeitos do Método de Varredura na

Detectabilidade

- Técnica de Inspeção

- Velocidade de Varredura

- Trajetória da Varredura

- Aparelhos Automáticos ou Semi Automáticos

- Uso de Registradores ou Telas Digitais

- Padrões de Referência de Trincas

- Trincas Empregadas em Padrões de

Referência

- Requisitos dos Padrões de Referência

- Padrões para Ensaios Específicos

- Descontinuidades Artificiais para Padrões

- Condições Simuladas para Padrões

- Entalhes Usinados por Eletroerosão

- Entalhes por Eletroerosão em Aços

Ferromagnéticos

- Entalhes por Corte

- Entalhes Usinados

- Escolha do Padrão de Referência para

Trincas

- Medição de Espessura

- Critérios de Aplicação

- Tipos de Medição

- Tipos de Medição (Continuação)

- Limitações Gerais da Medição de Espessura

de Chapas

- Sistemas de Ensaio

- Procedimentos de Medição de Espessura

- Medição da Espessura Metálica Total

- Aplicações da Medição da Espessura Total

- Limitações da Espessura Total

- Efeitos da Frequência na Medição da

Espessura Total

- Efeitos da Construção da Sonda

- Procedimento Operacional para Medição da

Espessura Total

- Preparo da Peça para Medição de Espessura

- Presença de Limitações Geométricas

- Seleção do Sistema de Ensaio

- Seleção da Frequência para Medição de

Espessura

- Ajustes do Aparelho

- Registro de Espessuras e Relatório de

Valores Rejeitados

- Padrões para Medição de Espessura Total

- Aplicações de Medição de Revestimentos

Condutores

- Aplicação Medição de Revestimentos

Condutores

- Efeitos das Propriedades do Material na

Medição da Espessura de Chapas

- Efeitos da Condição de Ensaio na Medição

da Espessura de Chapas

- Procedimentos para Medição da Espessura

de Chapas

- Padrões de Referencia de Espessura de

Chapas

- Medição de Revestimentos Não Condutores

- Revestimentos Não Condutores

- Base para Medição de Revestimentos Não

Condutores

- Efeitos na Impedância de Revestimentos

Não Condutores

- Influência das Propriedades dos

Materiais e da Frequência

- Sistemas de Ensaio de Revestimentos Não

Condutores

- Procedimentos para Medição de

Revestimentos Não Condutores

- Padrões para Medição de Revestimentos Não

Condutores

5 GERAL.

Todas

as inspeções para detecção de trincas ou outras falhas em serviço DEVEM ser

consideradas críticas. Cada inspeção em cada aeronave ou sistema de

armas deve ser abordada com o máximo cuidado e concentração. Sempre

configure seu instrumento de correntes parasitas de acordo com os

procedimentos estabelecidos. Certifique-se de verificar sua

configuração várias vezes durante a inspeção para garantir que seu

equipamento esteja respondendo corretamente. Reserve um tempo para

garantir que você tenha escaneado cuidadosamente toda a área de

inspeção, verificando suas varreduras duas vezes, se necessário. A

inspeção que você realiza pode ser a última linha de defesa contra uma

possível falha devido ao crescimento de fissuras. Não encontrar um

defeito em uma área durante uma inspeção anterior não diminui as

chances de ele se apresentar no futuro. Aborde cada inspeção como se

houvesse uma falha conhecida na área que você está inspecionando.

5.1

Ponto Nulo (de balanço ou de trabalho).

O ponto nulo é o local em um plano de impedância no qual o

instrumento de correntes parasitas é anulado ou zerado. Se anulado

corretamente em um material sem defeitos, o instrumento posicionará o

sinal (ponto) em um ponto específico da tela, e quaisquer alterações no

material, como uma trinca, farão com que o sinal (ponto) reflita uma

alteração na impedância elétrica no visor/tela.

5.2

Parâmetros. Há um grande número de parâmetros que podem ser definidos

em um instrumento de correntes parasitas. No entanto, os parâmetros

mais frequentemente ajustados pelos técnicos são frequência, ganho,

ângulo de fase, ponto de trabalho, escala da tela e filtros.

5.2.1 Frequência.

O

único parâmetro livremente ajustável em instrumentos modernos que afeta

as correntes parasitas é a frequência. Os demais parâmetros existem

apenas para melhorar a visibilidade da resposta do sinal no

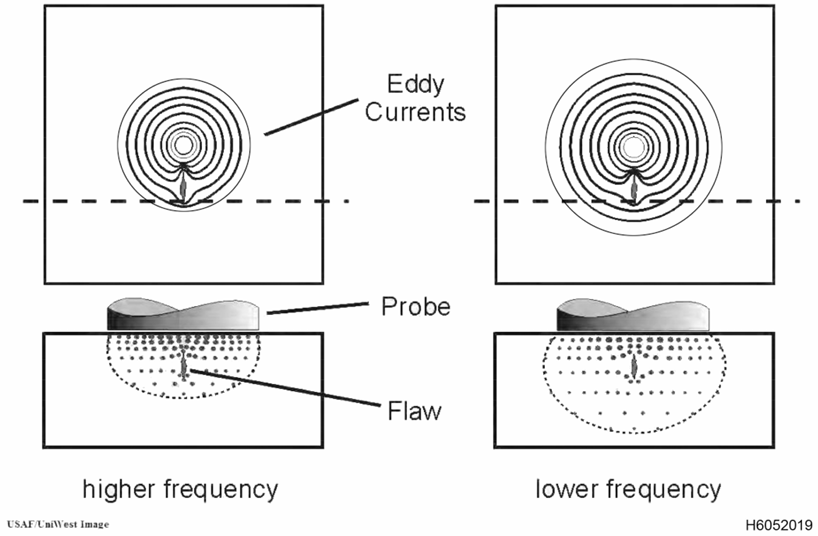

instrumento. Quanto menor a frequência, mais profundo o campo penetra

no material e, portanto, maior a profundidade na qual as correntes

parasitas fluem. No entanto, o campo não apenas se aprofunda, mas

também se espalha, ou seja, se dilui, resultando em menor sensibilidade

a pequenas variações (ver Figura 5.1). (N.T.: O uso de menor frequência

de ensaio implica em menor geração de correntes parasitas desde a

superfície na qual está a sonda.).

A propagação das correntes parasitas depende da condutividade do material e da frequência de acionamento do instrumento

5.2.1.1

A frequência não afeta a intensidade das correntes parasitas,

apenas a dispersão. (N.T.: Considerando o fenômeno de indução

eletromagnética essa afirmação não é valida). Alguns instrumentos podem

permitir o ajuste da

tensão de acionamento que passa pela bobina geradora, o que, por sua

vez, afeta a intensidade das correntes parasitas, resultando em maior

sensibilidade na detecção de falhas. Isso é independente do ajuste de

frequência.

5.2.2 Ganho.

O

ganho pode ser aumentado para obter uma resposta de sinal maior (ou

seja, para tornar um sinal pequeno mais visível) ou diminuído para

reduzir a resposta do sinal no visor do instrumento. No entanto,

aumentos no ganho aumentarão o "ruído" no visor do instrumento. O ruído

pode ser causado por diversos fatores: a eletrônica do instrumento (não

tão comum em instrumentos modernos), ruído do material resultante da

estrutura de grãos do material, ruído do material causado pela

alteração mecânica da superfície do material ensaiado, etc.

5.2.2.1

Alguns instrumentos possuem ganho H (dispersão X) ou ganho V (dispersão

Y) além do ganho regular. Esses dois ganhos permitem que o operador

aumente ou diminua o sinal independentemente na direção vertical ou

horizontal e são muito úteis para ajudar a distinguir sinais de ruído

de respostas defeituosas.

5.2.3 Ângulo de Fase.

Também

conhecido como rotação ou ângulo de rotação. Independente da fase real

das correntes parasitas, é uma configuração que permite ao usuário

rotacionar as respostas do sinal na tela do instrumento. Pode ser usado

para orientar a resposta do sinal ao levantar a sonda do material

(sinal de lift-off, ao usar uma sonda absoluta). Isso ajuda o usuário

a distinguir entre lift-off e um sinal provavelmente causado por uma

falha.

5.2.4 Sensibilidade/Detectabilidade.(não

disponível em todos os instrumentos)

Parâmetro que permite a ampliação

do visor do instrumento. Atua como o recurso de "zoom" da câmera; não

melhora a imagem, apenas a torna maior ou menor. É usado para definir a

escala do reticulado exibida na tela. Uma configuração comum é 1 Volt por

divisão de escala. Isso significa que um sinal com 2 divisões de escala

tem uma tensão de 2 Volts. Essa medida é usada para classificar sinais

como aceitáveis ou rejeitáveis.

Figura 5.1. Ilustração da distribuição das correntes parasitas com a frequência

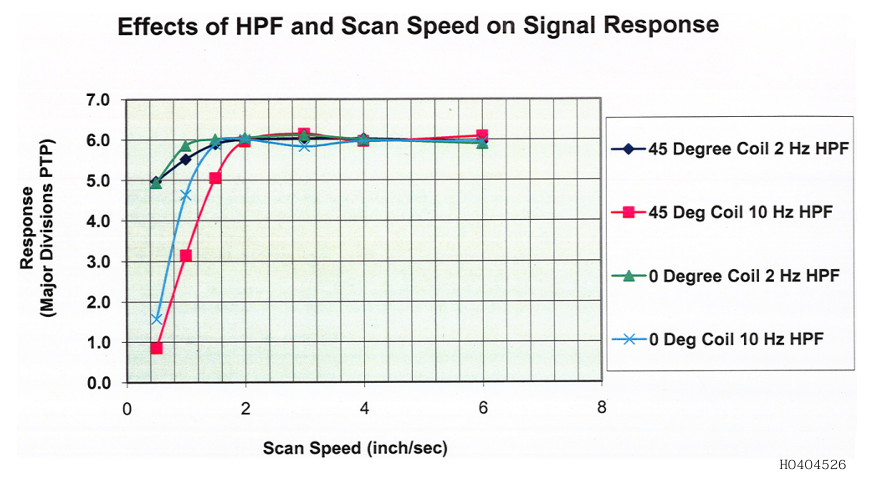

5.2.5 Filtros.

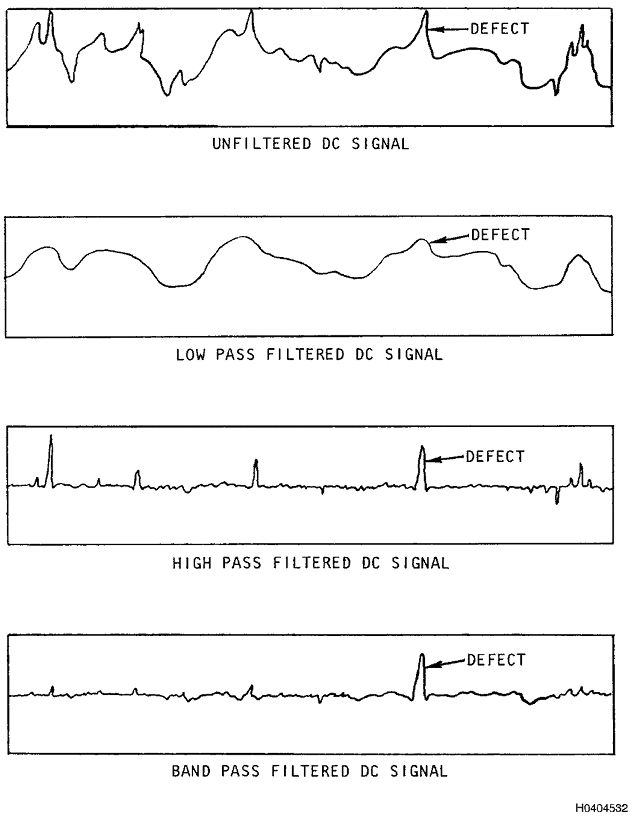

Usados

para filtrar sinais indesejados e melhorar a relação sinal-ruído,

conforme ilustrado na Figura 5.2. Três tipos de filtros podem ser

usados: passa-alta, passa-baixa e passa-faixa. Um filtro passa-alta

(HPF) remove sinais de baixa frequência e permite a passagem de altas

frequências, sendo útil para eliminar o efeito de variações graduais na

condutividade ou dimensões na resposta de correntes parasitas. Um

filtro passa-baixa (LPF) remove sinais de alta frequência e permite a

passagem de sinais de baixa frequência, sendo útil para reduzir os

efeitos do ruído eletrônico e da resposta de alta frequência de

frequências harmônicas relacionadas a variações na permeabilidade

magnética. Os filtros passa-faixa combinam filtros passa-baixa e

passa-alta para permitir uma resposta em uma faixa específica de

frequências e suprimir frequências acima e abaixo dessa faixa.

Figura 5.2. Ilustração dos efeitos de diferentes filtros no sinal de correntes parasitas.

- 5.3 Análise de modulação.

- Uma

técnica útil para separar sinais de interesse de outros sinais

baseia-se na análise dos sinais em função do tempo. Um bom exemplo

disso é o uso de um registro gráfico X e/ou Y (gráfico de faixas), onde a

amplitude do sinal aparece na escala vertical e os tempos em que o

sinal aparece e desaparece são monitorados na horizontal.

5.3.1

Um exemplo de análise de modulação é quando uma tela de instrumento de

plano de impedância é usado no modo de varredura durante uma inspeção

rotativa de furo de parafuso. Nessa técnica, o equipamento é

tipicamente configurado de forma que cada traço ao longo da varredura

represente uma rotação no furo. A posição do relógio de uma indicação

no furo pode ser determinada por sua localização ao longo da varredura.

De maior importância é a largura da indicação ou por quanto tempo ela

se desvia da linha de base. Neste exemplo, o tempo durante o qual a

indicação é detectada (largura) é usado para identificar se ela se deve

ou não a uma variável de interesse. Por exemplo, uma irregularidade em

um furo de parafuso produzirá uma indicação que dura um longo período,

enquanto uma trinca é muito estreita e produz uma indicação que dura um

curto período. Ambas as indicações podem ter a mesma amplitude, mas

talvez apenas a trinca seja de interesse. Um filtro eletrônico pode ser

usado para suprimir sinais de longa duração (baixa frequência),

deixando apenas a indicação de trinca (alta frequência) no visor para o

inspetor visualizar.

- Em

relação à análise de modulação, é importante entender que os termos

alta e baixa frequência se referem à duração da indicação, não à

frequência da corrente alternada na bobina.

5.3.2

A frequência de uma indicação é o recíproco do seu período de duração,

ou seja, quantos eventos (ciclos) desse tipo poderiam ocorrer em 1

segundo. Por exemplo, suponha que a indicação do furo fora de

circularidade discutida no Parágrafo 5.3.1 dure 0,1 segundo ao longo

da varredura, e a indicação da trinca dure 0,01 segundo ao longo da

varredura. A frequência f do sinal fora de circularidade seria 1/0,1 ou

10 ciclos/seg (Hz), e a da trinca seria 1/0,01 ou 100 ciclos/seg (Hz).

Um filtro passa-alta poderia ser ajustado em 50 Hz para suprimir sinais

abaixo de 50 Hz e permitir a exibição de sinais acima de 50 Hz. Como

também pode haver sinais com frequência mais alta do que a variável de

interesse, um filtro passa-baixa também pode ser usado para suprimir

ruído de alta frequência. Este filtro pode ser definido em 200 Hz para

o exemplo acima. Usados em conjunto, os filtros passa-alta e

passa-baixa formam o que é chamado de filtro passa-banda, o que

significa que apenas sinais com frequência acima de uma faixa

específica são exibidos. No exemplo acima, sinais acima de 200 Hz são

suprimidos pelo filtro passa-baixa, e sinais abaixo de 50 Hz são

suprimidos pelo filtro passa-alta. Para passar por ambos os filtros, o

sinal deve estar entre 50 e 200 Hz, ou durar de 0,005 a 0,02 segundos.

5.4

Resposta em Frequência.

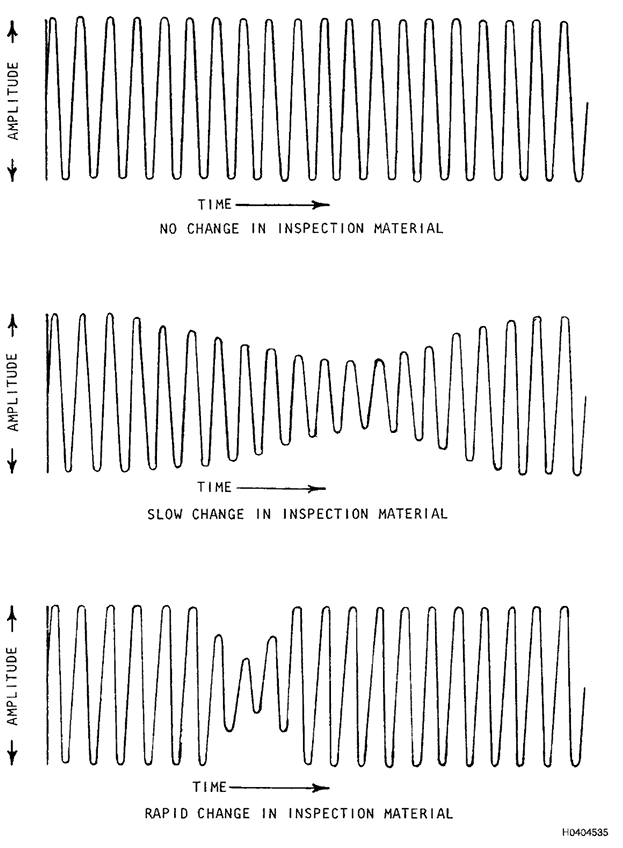

A análise de resposta em frequência é a forma

mais comum de análise de modulação. Durante o ensaio de correntes

parasitas, a impedância da bobina de ensaio permanece constante, desde

que não haja alteração nas condições de inspeção ou nas propriedades do

material. Quando ocorrem variações na impedância, as taxas de variação

na impedância e o sinal de corrente parasita resultante são

proporcionais às taxas de variação das propriedades do material e à

velocidade de varredura. Consequentemente, uma pequena fissura

proporcionaria uma rápida variação na impedância durante a varredura e

um sinal de corrente parasita de alta frequência correspondente. Esses

sinais podem ser visualizados em um monitor de vídeo ou em um

registrador gráfico de sinais em função do tempo. O efeito na

amplitude, ao encontrar diferentes tipos de variações do material e ao

varrer a uma velocidade constante, é mostrado na Figura 5.3. Uma

rápida mudança de sinal costuma ser um bom indicador de uma pequena

falha ou de uma mudança abrupta nas características do material. Uma

lenta mudança de sinal geralmente indica uma mudança gradual nas

dimensões, elevação ou alguma outra propriedade.

Figura 5.3. Efeito de variáveis materiais na magnitude da corrente alternada na bobina de ensaio com velocidade de varredura constante

5.5 Inspeção de furos de fixação.

5.5.1

Trincas em Paredes de Furos de Fixadores. Uma aplicação comum da

inspeção por correntes parasitas em estruturas de aeronaves é a

detecção de trincas em furos ou paredes de fixadores. Essas trincas são

geralmente geradas por fadiga, corrosão sob tensão ou uma combinação de

fadiga e corrosão. O progresso dessas trincas costuma ser lento no

estágio inicial, onde a detecção precoce pode prevenir possíveis falhas

catastróficas.

5.5.1.1 Trincas por Fadiga.

As

trincas por fadiga são geralmente causadas por carregamentos cíclicos

repetidos sobre uma estrutura, com níveis de tensão inferiores aos

necessários para a deformação visível. Como a tensão se concentra em

áreas de fragilidade localizada, como furos, as trincas por fadiga

frequentemente se iniciam nesses pontos. As trincas geralmente se

propagam normal à direção da tensão máxima de tração aplicada. A

seguir, descrevemos dois tipos de fadiga:

- Fadiga

de Alto Ciclo (FAC). FAC geralmente significa que a tensão aplicada é

baixa em comparação com a resistência à tração final do material, mas

submetida a um número muito alto de ciclos (exemplos: tensões de

vibração ou turbulência do ar).

- Fadiga

de Baixo Ciclo (LCF). LCF geralmente significa que a tensão aplicada é

alta em comparação com a resistência à tração final do material, mas

submetida a um número muito baixo de ciclos (exemplos: tensões de

decolagem e pouso).

5.5.1.2 Trincas por Corrosão sob Tensão.

Trincas

por corrosão sob tensão ocorrem sob a influência combinada de uma

tensão de tração e de um ambiente corrosivo sobre um material

suscetível à corrosão sob tensão. A tensão de tração pode resultar de

uma tensão aplicada ou de uma tensão residual. A umidade do ar

combinada com um ambiente suficientemente corrosivo pode, em alguns

casos, causar trincas por corrosão sob tensão. Além disso, a combinação

de fadiga cíclica na presença de trincas por corrosão pode causar o

rápido crescimento das trincas.

5.5.1.3 Acabamento e Dimensões da Parede do Furo.

O

acabamento e as dimensões da parede do furo influenciam tanto a

ocorrência quanto a detectabilidade de trincas em furos de fixadores.

Danos na parede do furo, como arranhões, trepidações e ranhuras criadas

durante a fabricação, podem criar concentrações adicionais de tensão na

parede do furo e fornecer locais preferenciais para o início de

trincas. Parafusos frouxos causados por furos superdimensionados ou

fora de circularidade permitem movimento na área do furo e permitem

ação de fadiga. Essas mesmas condições podem influenciar a

confiabilidade da inspeção. Durante a inspeção, danos severos à parede

do furo resultam em indicações de correntes parasitas que podem não ser

separáveis das indicações de trincas. O lift-off excessivo devido

a condições fora de circularidade também pode mascarar indicações de

trincas. Todas essas condições podem ser criadas durante os processos

de fabricação no furo ou como resultado da ação de fadiga durante o

serviço e da remoção do parafuso.

5.5.1.4

Efeitos de Borda. Muitas trincas em furos de fixadores ocorrem na borda

do furo ou próximo a ela. Estruturas adjacentes, raios de escareamento

e rebarbação não uniformes e danos nas bordas do furo aumentam o ruído

de fundo e diminuem a relação sinal-ruído. Isso leva a uma perda geral

de detecção de trincas na borda dos furos. Outros efeitos na

detectabilidade de trincas resultam da presença de outros metais

adjacentes à borda do furo. Superfícies escareadas também limitam a CP

por técnicas manuais adjacentes às bordas do furo.

5.5.2

Preparação dos Furos dos Parafusos. Os furos nas superfícies de contato

devem ser realinhados antes da inspeção CP ou perfurados com um

diâmetro maior, que seja concêntrico através das peças de contato.

Antes de realizar a inspeção dos furos dos parafusos, todo o material

estranho deve ser removido do furo. Materiais estranhos podem incluir

selantes, lubrificantes, lascas de metal e lascas de tinta.

Normalmente, esse material pode ser removido com cotonetes e um

solvente adequado. Furos severamente danificados durante o serviço ou

durante a inserção/remoção de fixadores podem exigir alargamento antes

da inspeção CP. Se alargamento for necessário, entre em contato com o

engenheiro responsável pelo componente para obter um método aprovado.

5.6 Aparelho de inspeção de furos de fixadores

CUIDADO

Em

geral, a capacidade de detecção da varredura manual de furos de

parafusos é significativamente menor do que a varredura automática de

furos de parafusos e, portanto, NÃO DEVE substituír a varredura

automática, a menos que especificado em procedimentos específicos da

peça ou em autorização específica por escrito da autoridade de

engenharia responsável.

5.6.1 Escaneamento manual de furos de parafusos.

CUIDADO

A

inspeção automática por correntes parasitas em furos de parafusos

(BHEC-Bolt Hole Eddy Current) DEVE ser realizada de acordo com a Ordem Técnica (TO=Technical Oredere) do sistema de armas

aplicável e/ou o pacote de trabalho apropriado na TO 33B-1-2 para o

procedimento específico a ser executado. Salvo indicação em contrário,

a TO específica do sistema de armas sempre tem precedência sobre as

recomendações do fabricante ou qualquer TO geral.

Quando

utilizada, a varredura manual dos furos de parafusos é realizada em

níveis especificados em toda a profundidade do furo. A inspeção

geralmente é iniciada com o centro da bobina da sonda posicionado

imediatamente dentro da borda superior ou inferior do furo, de modo que

a borda externa da bobina fique nivelada com a superfície da peça. A

posição da bobina da sonda é ajustada para o nível especificado abaixo

do colar da sonda, e a sonda é inserida no furo até que o colar da

sonda encoste na superfície da peça. Ocasionalmente, a corrosão sob

tensão intergranular (IGC) pode ocorrer ao longo de um plano

aproximadamente paralelo à superfície da peça. A indicação desse tipo

de corrosão é semelhante a um furo de formato elíptico ou a uma mudança

lenta na condutividade. A aplicação incorreta da filtragem passa-faixa

pode mascarar a presença de IGC.

5.6.2

Varredura Automatizada de Furos de Parafuso.

A varredura automática é

normalmente usada para inspeção de furos de parafuso devido à maior

capacidade de detecção em relação à varredura manual. Este equipamento

fornece uma unidade de varredura portátil que aciona uma sonda propciando uma varredura em um

padrão helicoidal ao longo do furo, ou gira a sonda em altas revoluções

por minuto, a uma velocidade constante enquanto o operador indexa/movimenta a

sonda através do comprimento do furo. O equipamento que gira a sonda em um padrão

helicoidal é chamado de dispositivo de varredura ("scanner") de rotação translacional. Muitas vezes,

"scanners" de alta velocidade não têm movimento translacional

automatizado e dependem da velocidade na qual o operador empurra e puxa a

sonda para dentro e para fora do furo. Os resultados podem ser

armazenados em um registrador de gráfico de tiras ou exibidos em um

visor digital.

5.6.2.1

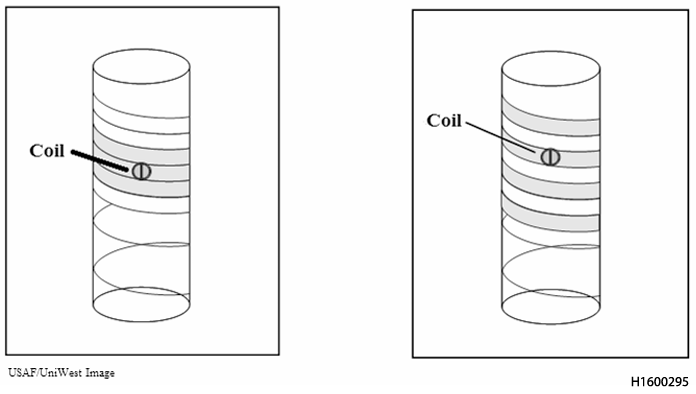

O "Scanner" Rotativo.

O "scanner" gira a sonda do furo de parafuso a uma

determinada velocidade, que foi definida no instrumento durante a

configuração. A sonda deve ser inserida no furo do fixador e

movimentada no furo a uma velocidade lenta o suficiente para que a

bobina na sonda

escaneie toda a superfície da parede do furo em uma espiral fechada,

garantindo assim 100% de cobertura da superfície (veja a Figura 5.4).

5.6.3

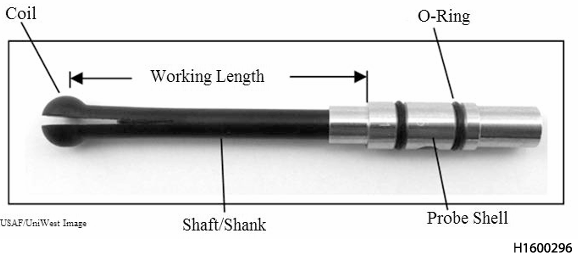

Sondas Rotativas para Furo de Parafuso.

O projeto mais comum de sonda

para furo de parafuso é mostrado na Figura 5.4. A sonda consiste em

uma carcaça com um conector de 4 pinos e um corpo principal. A carcaça

possui dois anéis de vedação que prendem e centralizam a sonda no

receptáculo do conector do "scanner". Itens fornecidos pelo fabricante

como parte integrante da construção ou operação da sonda, como anéis de

vedação, NÃO DEVEM ser removidos. O corpo consiste em uma haste com uma

esfera integrada na extremidade, chamada de "cabeça". A haste é

bipartida e uma das duas metades da cabeça contém a bobina do sensor. A

cabeça bipartida proporciona flexibilidade de mola para garantir que a

bobina do sensor possa ficar o mais próximo possível da parede do furo

do fixador. Ao escolher uma sonda para furo de parafuso, o diâmetro da

esfera deve ser igual ou ligeiramente menor que o do furo do fixador a

ser inspecionado. Isso proporciona o melhor ajuste após a haste ser

aberta e a fita aplicada.

Figure 5.4. Técnica adequada para garantir 100% de cobertura (esquerda), cobertura incompleta (direita)

Figure 5.5. Projeto Típico de Sonda para Furo de Fixador

5.6.3.1

Há uma variedade de outros projetos, como sondas com cabeças cônicas ou

cilíndricas, ou sem cabeça alguma. No entanto, estudos demonstraram que

a sonda em formato de esfera fornece ótima detectabilidade de falhas em

todo o furo de um fixador, incluindo na borda de ambas as extremidades

abertas. O formato de esfera ajuda a garantir que a bobina esteja em

contato com a parede do fixador, mesmo que a sonda não esteja

totalmente alinhada com o eixo do furo.

5.6.3.2

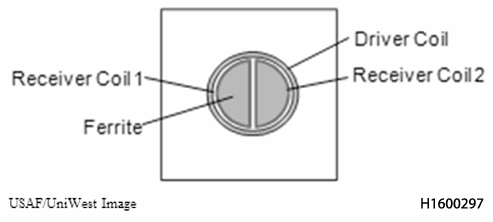

A Figura 5.6 mostra a configuração típica da bobina em uma sonda para

furo de parafuso. A bobina consiste em duas bobinas receptoras, cada

uma enrolada em uma ferrite em formato de D. As bobinas receptoras são

então colocadas lado a lado e uma bobina condutora é enrolada em torno

de ambas. Os receptores são conectados de forma diferente (polos elétricos). Isto

significa que se a Bobina Receptora 1 "vê algo", ela causa uma resposta

de sinal ascendente. Se a Bobina Receptora 2 vê algo, ela causa uma

resposta de sinal descendente. Este tipo de bobina é chamado de

reflexão diferencial

Figura 5.6. Configuração da Bobina em uma Sonda de Furo de Parafuso

5.6.3.3

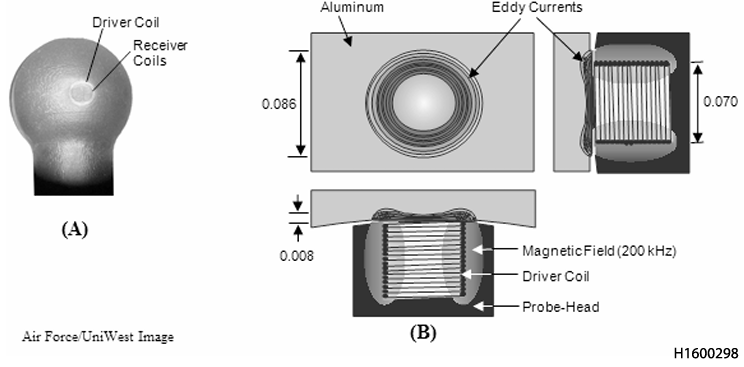

A Figura 5.7 (A) mostra uma sonda de furo de parafuso típica com uma

bobina de reflexão diferencial padrão "D50". A bobina excitadora ("driver") é a bobina

mais externa. A bobina "driver" gera um campo magnético alternado que

penetra no material condutor. O material reage gerando correntes

parasitas cujo campo se opõe ao campo eletromagnético primário. Como o

campo magnético de entrada é espalhado, ou seja, o campo efetivo tem

uma área efetiva muito maior do que apenas o diâmetro da bobina, as

correntes parasitas são assim mais espalhadas.

5.6.3.4

A Figura 5.7 (B) mostra a distribuição de correntes parasitas para a

sonda mostrada na Figura 5.7 (A). As correntes parasitas fluem no

mesmo padrão circular que os enrolamentos da bobina condutora, são mais

fortes perto dos enrolamentos da bobina e dissipam-se lentamente no

material condutor. A figura mostra a extensão e a profundidade externas

das correntes até o ponto em que sua intensidade atinge 37% da

intensidade na superfície (profundidade de penetração padrão). Neste

exemplo, o resultado é que, em um componente de alumínio a 200 kHz, uma

sonda com uma bobina condutora de 0,070" de diâmetro gerará um campo de

correntes parasitas com cerca de 0,008" de profundidade no material e

terá uma área de detecção que se estende por aproximadamente 0,086" de

diâmetro.

Figure 5.7. Exemplo de (A) Sonda de Furo de Parafuso e (B) Bobina de Excitação e Geração de Correntes Parasitas

.

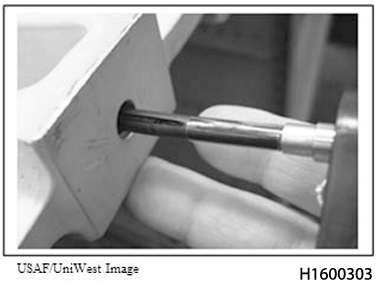

5.7

Ajuste da Sonda.

Uma sonda que se encaixe corretamente dentro do furo

é essencial para o desempenho da inspeção. Uma sonda mal ajustada

vibrará no furo, resultando em elevação excessiva e ruído de sinal.

CUIDADO

Somente

sondas do tamanho correto DEVEM ser usadas para realizar a inspeção de

furos de parafusos por correntes parasitas. A inspeção com uma sonda

mal ajustada pode resultar em indicações de trincas perdidas.

5.7.1 A seguir apresenta-se uma sequência simples para garantir um bom encaixe da sonda:

- a. Meça o diâmetro do furo do parafuso se você não o souber;

- b. Selecione uma sonda com uma faixa de tamanho que se ajuste ao furo do parafuso;

- c. Aplique a sonda com fita adesiva; não a insira no scanner;

- d. Insira-a no furo;

- e.

Se a sonda puder quase ficar em pé no furo (se o furo for vertical e

para baixo), ou ficar pendurada dentro do furo (se o furo for vertical

e para cima), ou não escorregar para fora do furo (se o furo for

horizontal) e se você ainda puder girá-la suavemente com a mão, o

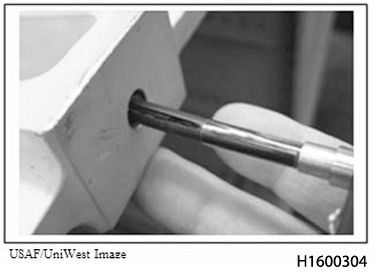

encaixe da sonda está correto (Figura 5.8)

- f.

Se o encaixe não estiver correto, coloque um pouco de espuma não

condutora ou material emborrachado na fenda da haste da sonda e tente

novamente.

Figura 5.8. Verificando o ajuste da sonda no furo

5.8

Aplicação de Fita na Sonda.

As sondas para furos de parafusos são

fabricadas com diversos tipos de materiais, dependendo do tipo e do

fabricante da sonda. Algumas sondas são mais duráveis do que outras.

Sondas feitas de plástico macio podem se desgastar e expor os

enrolamentos da bobina em apenas alguns usos, portanto, é sempre

aconselhável carregar uma sonda extra. Uma maneira de proteger a bobina

é usar fita de "teflon" para cobri-la. Parte da duração de uma sonda e

das respostas que você observa durante uma inspeção depende da forma

como você a aplica. Deve ser usada fita com espessura entre 2,5 e 3,5

mils (0,0025-0,0035 polegadas), levemente elástica e com revestimento

adesivo. A maneira correta de aplicar a fita é enrolá-la completamente

ao redor da metade da bobina de uma sonda bipartida. As extremidades da

fita devem ser dobradas entre a sonda bipartida. A sonda bipartida

proporciona uma ação semelhante a uma mola para garantir que a bobina

mantenha contato com a superfície do furo durante a rotação. Portanto,

a fita NÃO DEVE ser enrolada completamente em torno de ambas as metades

da divisão, pois isso impedirá que a sonda se ajuste ao furo. A Figura

5.9 mostra um exemplo de uma sonda com fita aceitável. Neste exemplo,

a fita cobre suavemente a metade da bobina da sonda sem rugas e as

extremidades da fita são dobradas entre a divisão. A Figura 5.10 e a

Figura 5.11 mostram exemplos de aplicação de fita inaceitável. A Figura

5.10 mostra a fita cobrindo apenas metade da bobina, o que permitiria

que as bordas da fita subissem durante a rotação da sonda no furo, e a

Figura 5.11 mostra a fita que não foi aplicada suavemente e está

enrugada.

Figura 5.9. Exemplos de Sondas de Furo de Parafuso Com Aplicação Aceitavel da Fita

Figura 5.10. Aplicação de Fita Inaceitável (Incompleta)

Figura 5.11. Aplicação de Fita Inaceitável (Enrugada)

5.9

Compensação de Lift-off (afstamento sonda-peça) para Inspeção de Furo de Parafuso.

A

compensação de levantamento para inspeção de furo de parafuso depende

da qualidade da superfície e das dimensões do furo. A compensação de

lift-off ideal é aquela que apenas suprime as variações de lift-off

dentro do furo, mas não fornece compensação excessiva. A compensação

excessiva de lift-off pode reduzir a sensibilidade e aumentar o ruído.

Ao usar sondas sem blindagem, quantidades específicas de compensação de

lift-off podem ser obtidas usando um calço entre a bobina da sonda do

furo do parafuso e a parede do furo. A espessura do calço deve ser

igual à quantidade de compensação de lift-off desejada e deve ser

relativamente resistente para evitar rasgos durante a inserção e

remoção da sonda. Fita de Teflon DEVE ser usada para essa finalidade. A

compensação de lift-off geralmente é realizada no furo em um ponto

afastado da borda ou no centro se a espessura da peça for inferior a

1,25 cm. Mais tolerância nas configurações de compensação de lift-off é

permitida ao usar equipamento de varredura automática ou sondas

blindadas.

5.10

Configurações do Aparelho ("Calibração").

As configurações de ajuste do

instrumento antes da inspeção são baseadas na resposta a um padrão de

referência especificado. Uma ampla variedade de padrões de ensaio é

utilizada para inspeção de furos de parafusos. Eles incluem peças

trincadas, entalhes usinados por eletroerosão (EDM), entalhes cortados

com serra de joalheiro, diferenças na condutividade dos padrões de e uma

infinidade de outros padrões com entalhes e/ou trincas maiores. Cada

procedimento individual DEVE especificar o padrão a ser utilizado e a

resposta necessária em termos de deflexão do medidor ou tamanho da

indicação em um registrador, registro gráfico ou visor do instrumento.

Quando for necessário encontrar pequenas falhas e existir a

possibilidade de diferentes tipos de sondas (tamanho da bobina e

frequência) serem utilizados, é necessário utilizar uma referência com

as mesmas dimensões aproximadas das falhas a serem detectadas, como

entalhes por eletroerosão.

5.11

Velocidade e a Trajetória de Varredura.

A velocidade e a trajetória da varredura

devem ser considerados durante a configuração do procedimento. Isso é

especialmente importante com a varredura manual, pois a resposta da

sonda com a varredura manual não será a mesma que durante a varredura

automatizada. A distância entre as varreduras ou o incremento de

varredura é determinado pelo tamanho mínimo de trinca necessário para

ser detectado. Durante a varredura manual, o procedimento de varredura

é repetido após a colocação da bobina da sonda em cada posição de

varredura até que todo o comprimento do furo tenha sido inspecionado.

Ao inspecionar múltiplas camadas, a inspeção deve ser realizada nos

materiais de cada camada adjacente a cada interface. Quando a posição

específica da interface entre camadas de material similar não for

conhecida, sua posição pode ser estabelecida passando a sonda pela

interface e marcando a posição de deflexão máxima do sinal. A

configuração e a inspeção DEVEM ser realizadas usando a mesma

velocidade e padrão de varredura para garantir a melhor resposta do

sinal e a máxima cobertura da varredura.

Ao inspecionar um furo, a sonda deve ser guiada

para dentro do furo de forma que o eixo da sonda esteja alinhado com o

eixo do furo (consulte as Figuras 5.12 e 5.13). Isso pode ser difícil

de fazer, especialmente ao monitorar a tela do instrumento ao mesmo

tempo. Se a sonda não estiver alinhada corretamente, a bobina pode não

tocar a superfície do furo do parafuso, impedindo uma inspeção eficaz.

A sonda também pode oscilar ou vibrar, causando ruído excessivo.

Figura 5.12. Alinhamento correto da sonda.

Figura 5.13. Alinhamento incorreto da sonda.

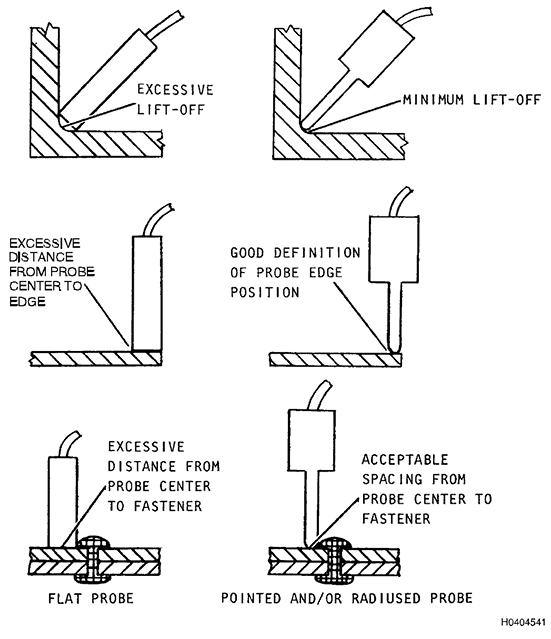

5.13

Espaçamento entre Sonda e Borda.

Ao inspecionar pequenas trincas

originadas nas bordas, o espaçamento entre sonda e borda pode se tornar

uma preocupação. Algumas abordagens para superar essas preocupações

são: aumentar a frequência da fonte geradora de correntes parasitas,

reduzir o tamanho físico da bobina e adicionar blindagem ao redor da

bobina da sonda. Blindagem adicional permitirá uma inspeção mais

próxima da borda devido ao menor volume de material detectado e

resultará em maior sensibilidade a falhas menores. O espaçamento entre

sonda e borda torna-se ainda mais preocupante quando a borda da peça

está em contato com uma peça ferromagnética, como um rolamento ou

bucha. Novamente, minimizar o volume de material detectado pela sonda

aliviará algumas dessas preocupações irrelevantes e otimizará a

resposta do sinal.

5.14

Interpretação do Sinal de Correntes Parasitas em Furos de Parafuso.

Um

dos requisitos mais importantes para detectar uma pequena trinca é que

a bobina passe sobre a trinca. Indiscutivelmente, a capacidade do

técnico de interpretar as respostas do sinal de correntes parasitas é

igualmente crucial para uma inspeção bem-sucedida. Para avaliar

completamente qualquer indicação, os técnicos devem utilizar as telas

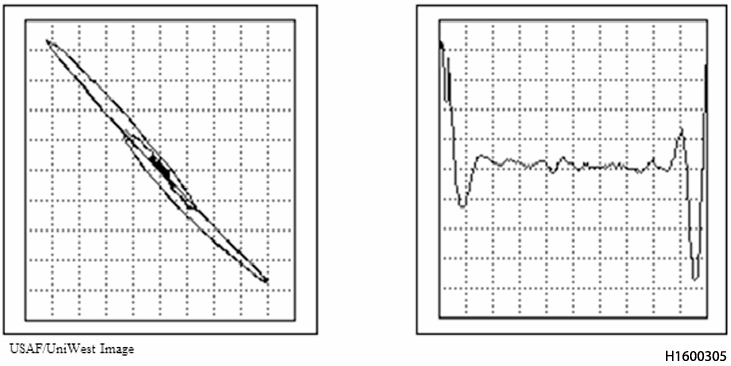

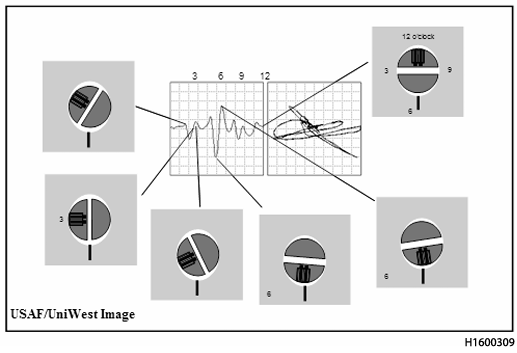

de plano de impedância e de varredura (registro gráfico, Figura 5.14).

O plano

de impedância fornece as informações de fase, permitindo que o técnico

avalie se uma indicação é decorrente de ruído ou de uma trinca. A

Figura 5.15 ilustra por que a passagem de uma sonda de reflexão

diferencial sobre uma trinca resulta em uma indicação em forma de oito

("Lissajous") ou de circuito duplo na tela do instrumento. O registro

gráfico da varredura

mostra quantas indicações de falha estão presentes e, se configurado

corretamente, em qual posição circunferencial, a partir de um ponto de

referência, cada falha está localizada no furo. Usados em conjunto,

as telas de plano de impedância e de varredura permitem que o

técnico determine a orientação do sinal presente, quantas falhas estão

presentes e sua posição circular dentro do furo do fixador.

Figura 5.14. Mostrador do Plano de Impedância (Esquerda) e Registro Gráfico da Varredura (Direita).

Figura 5.15. Respostas do Sinal de Correntes Parasitas em Furos de Parafusos a Partir de uma Trinca

- A medida que a sonda se move através da trinca o

trajeto das correntes parasitas vai se modificando com a circulação ao

redor e abaixo da trinca;

- Essa mudança é detectada pela bobina receptora 1 e como resultado, o ponto no plano de impedância move-se para cima;

- Com a continução de movimentação da sonda, a

distorção da corrente causa uma resposta máxima na bobina receptora 1 e

a resposta no plano de impedância alcança o máximo;

- Quando a trinca se localiza no centro das bobinas, o

fluxo de corrente se modifica ao redor da trinca e a distorção atinge

seu máximo;

- Entretanto, nessa posição ambas as bobinas sensoras

estão "sentindo" o mesmo campo e porque estão enroladas em

sentido contrário , o sinal resultante é zero (resposta nula);

- A medida que a sonda se move mais ainda, a bobina

receptora 2 agora "sente" a distorção da corrente e

como resultado o sinal no plano de impedâncias se move para baixo;

5.14.1

Furos Excêntricos.

Os efeitos de furos fora de circularidade ocorrem

frequentemente, dificultando muito a interpretação do

sinal e podendo levar a falsas indicações ou à perda de trincas. É

muito importante medir os furos dos fixadores antes da inspeção, caso

suspeite de uma condição fora de circularidade. Estudos demonstraram

que a detecção de trincas ainda é possível em diâmetros nominais abaixo

de 0,006 a 0,008 polegadas fora de circularidade; no entanto, a

resposta do sinal de trinca é ligeiramente distorcida. Acima desses

valores, os sinais de trinca são geralmente distorcidos, não são

distinguíveis do ruído e os níveis de ruído excedem os limites de

rejeição. Em aplicações em campo, furos fora de circularidade

normalmente apresentam níveis inaceitáveis de ruído de sinal. Os

parágrafos a seguir descrevem alguns dos efeitos observados nas

respostas de sinal de furos fora de circularidade.

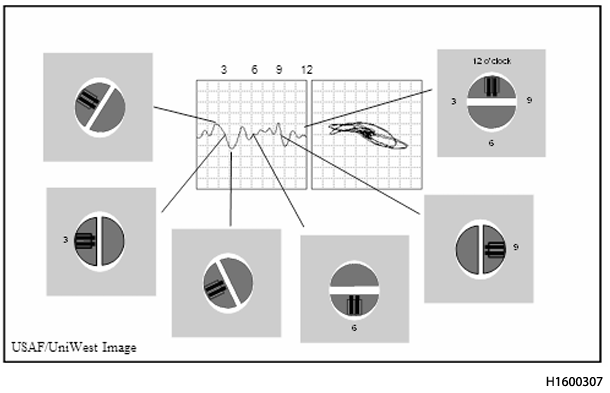

5.14.1.1

Resposta "Tipo Poço" ["GOAL POST"} (sem trinca). À medida que a sonda gira no furo do

fixador, ela se comprime ao entrar na seção estreita (3-9 horas). Ao

entrar na seção mais larga (6-12 horas), ela se expande, mas a bobina

pode não tocar mais a superfície e, portanto, sofre lift-off O

resultado é um padrão semelhante a um poço no visor registro gráfico de varredura e

uma indicação no visor de impedância semelhante a uma indicação de

trinca, mas em um ângulo de fase diferente (Figura 5.16). Esse ruído

excessivo de lift-off é rejeitável .

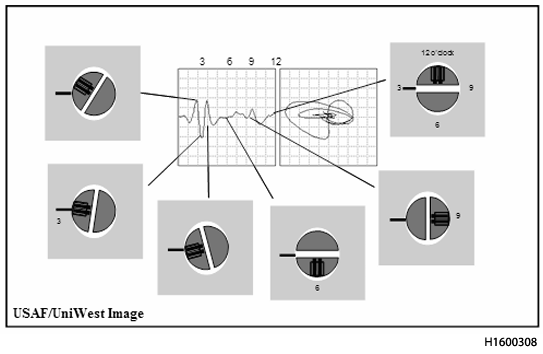

Figura 5.16. Resposta tipo poço em alumínio.

5.14.1.2

Resposta de ruído excessivo. Se houver uma trinca na seção estreita de

um furo fora do círculo, o efeito de lift-off pode mascarar ou

distorcer a resposta do sinal da trinca, dificultando a interpretação

da resposta da trinca (Figura 5.17). Mesmo que uma indicação semelhante

a uma trinca não estivesse presente, o furo na Figura 5.17 ainda seria

rejeitável, com base no ruído de elevação excessivo

Figura 5.17. Resposta de Ruído Excessiva em Alumínio

5.14.1.3

Ruído Excessivo e Resposta a Trincas. Se houver uma trinca na seção

mais larga de um furo fora de circularidade, o efeito de lift-off tem

dois efeitos: pode mascarar ou distorcer a resposta do sinal da trinca

e reduz a amplitude do sinal (Figura 5.18). O furo na Figura 5.18 seria

rejeitável com base no ruído e devido a uma indicação semelhante a uma

trinca. Se o furo estiver severamente fora de circularidade, o efeito

de lift-off pode ser tão grande que não há resposta perceptível da

trinca.

Figura 5.18. Ruído Excessivo e Resposta a Trincas em Alumínio

5.15 Furos de Fixadores Não Removíveis.

5.15.1

Inspeção Aplicação de Furos de Fixadores.

Se um fixador não puder ser

removido de um furo devido ao seu tipo ou localização, a inspeção ao

redor do fixador pode ser realizada para detectar trincas que se

desenvolvem sob a cabeça ou porca do fixador. O tamanho das trincas

detectáveis depende da distância que deve ser mantida entre a sonda e

a borda do fixador. Em muitos aspectos, essa aplicação é semelhante à

inspeção de trincas na borda de aberturas e recortes. Sondas grandes de

baixa frequência e sondas reflexivas deslizantes também podem ser

escaneadas sobre fixadores escareados e identificar trincas na 1ª, 2ª e

3ª camadas.

5.15.2

Espaçamento entre Sonda e Fixador.

Se necessário apenas para detectar

trincas relativamente grandes, como aquelas que se estendem entre dois

fixadores, a inspeção por correntes parasitas geralmente pode ser

realizada a uma distância suficiente das cabeças dos fixadores para

eliminar seu efeito na resposta das correntes parasitas. Quando

pequenas trincas precisam ser detectadas, a sonda deve ser posicionada

mais próxima da borda do fixador, e a distância entre a sonda e o

fixador deve ser mantida constante durante a varredura. Quando

fixadores fabricados com materiais magnéticos, como aço, são usados

em peças não magnéticas, um espaçamento relativamente grande deve ser

usado. Além disso, sondas blindadas podem ser usadas para minimizar a

distância entre a sonda e o fixador, permitindo a inspeção próxima ao

fixador.

5.15.3

Guias de Varredura ao Redor de Fixadores Não Removíveis.

Para fixadores

não ferrosos (não magnéticos), a cabeça do fixador pode ser usada como

guia da sonda. Somente os fixadores que se projetam da superfície da

peça e são concêntricos com o furo podem ser usados como guias. Para

fixadores com cabeças não concêntricas com os furos, como cabeças

hexagonais e serrilhadas, um colar acoplado à cabeça do fixador pode

ser usado como guia de varredura. A maioria das sondas blindadas pode

ser varrida ao redor de fixadores de aço sem a necessidade de um colar.

Os gabaritos devem ser posicionados concêntricos à cabeça do fixador

para garantir uma resposta relativamente consistente de um material sem

defeitos à medida que a sonda é guiada ao redor do fixador.

5.15.4

Seleção da Sonda.

Assim como em muitas outras aplicações de detecção de

falhas, recomenda-se o uso de sondas de raio de pequeno diâmetro. Essas

sondas permitem melhor visibilidade da localização da bobina da sonda e

maior flexibilidade no estabelecimento do espaçamento entre a sonda e o

fixador. Sondas de raio também são menos suscetíveis do que sondas de

superfície plana a variações de elevação com mudanças no ângulo entre a

sonda e a superfície.

5.15.5

Normas para Furos de Fixadores Não Removíveis.

Sempre que possível, as

normas para inspeção ao redor das cabeças de fixadores não removíveis

devem reproduzir o mais fielmente possível as condições da área de

inspeção. Caso não estejam disponíveis amostras trincadas que

representem o tamanho mínimo de trinca a ser detectado, podem ser

utilizadas ranhuras de eletroerosão cortadas nas bordas dos furos na

norma de referência. O material, a geometria, o tamanho do furo, o tipo

de fixador e a instalação devem ser os mesmos para a peça de referência

e para a área de inspeção, a menos que tenha sido estabelecida

correlação prévia com outras referências disponíveis. A duplicação da

geometria da peça na referência minimiza as diferenças de resposta

entre as referências e as trincas na peça.

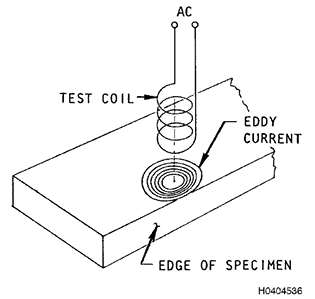

5.16 Filetes e Cantos Arredondados.

5.16.1

Bordas (Incluindo Cantos e Raios).

Para a maioria das técnicas de

correntes parasitas, o fluxo é circular e paralelo à superfície da

peça. Se o fluxo de correntes parasitas interceptar uma borda, canto ou

raio da peça, o padrão circular é interrompido e as correntes parasitas

ficam confinadas a um volume menor. Essa ação altera a magnitude e a

distribuição das correntes parasitas e é conhecida como efeito de borda

(Figura 5.19). Conforme ilustrado, a densidade de corrente será

ligeiramente maior na borda da peça do que no interior. Isso resultará

em um ligeiro aumento na sensibilidade a descontinuidades localizadas

na borda.

5.16.2

Ocorrência de Trincas.

Cargas de flexão repetidas aplicadas a filetes e

raios (cantos arredondados) de uma peça podem levar a trincas por

fadiga. Trincas por fadiga geralmente ocorrem paralelas ao raio. Em

raios moldados, a trinca geralmente ocorre perto do centro do raio,

onde há afinamento máximo. Em filetes usinados ou raios de perfis

extrudados onde a espessura da peça é maior no centro do raio, é mais

provável que ocorram trincas de fadiga no ponto tangente ao raio. Às

vezes, podem ocorrer trincas por corrosão sob tensão nos raios e

filetes de peças usinadas onde são aplicadas tensões de tração ou áreas

com tensões de tração residuais são expostas. A trinca por corrosão sob

tensão é frequentemente promovida pelo acúmulo de umidade nesses

filetes e raios.

Figura 5.19. Distorção do Fluxo de Correntes parasitas na Borda de uma Peça

5.16.3

Requisitos de Equipamento para Filetes e Raios.

Em geral, nenhum

equipamento especial é necessário para a inspeção de filetes e raios.

Uma inspeção adequada pode ser realizada usando instrumentos de

correntes parasitas com uma sonda de ponta de raio ou um sistema de

ensaio equivalente. O raio da ponta da sonda deve ser menor que o raio

do filete a ser inspecionado para garantir um contato relativamente

constante entre a sonda e a peça e, assim, evitar variações excessivas

no levantamento. Para a inspeção das bordas de raios ou filetes, é

recomendável usar uma régua plástica fina para manter o espaçamento

entre a sonda e a borda no filete. Ocasionalmente, um dispositivo de

fixação semelhante ao usado para os raios de assento do talão em rodas

pode ser usado para filetes e raios. Dispositivos de fixação reduzem o

tempo de inspeção, melhoram a detectabilidade da inspeção e garantem

uma cobertura completa.

5.16.4

Padrões de Referência para Filetes.

O melhor padrão de referência é uma

peça real com uma falha real. Se isso não puder ser obtido, um corpo de

prova que represente a configuração da peça a ser testada deve ser

usado para a configuração. Portanto, é preferível ter um padrão do

mesmo material, acabamento e raio do filete a ser ensaiado. Uma ou

várias falhas podem ser colocadas na área de inspeção do padrão de

referência. O padrão deve conter pelo menos uma falha igual ou menor

que o tamanho de falha exigido pela inspeção. Padrões planos podem ser

usados se um padrão com a configuração necessária não estiver

disponível. A resposta de padrões planos difere muito pouco da resposta

de trincas ou ranhuras em filetes ou superfícies curvas se uma sonda de

raio com diâmetro substancialmente menor que o raio do filete for

usada. Ranhuras nas bordas não são intercambiáveis com ranhuras

localizadas longe da borda.

5.17 Corrosão.

5.17.1

Requisitos do Sistema de Ensaio para Detecção de Corrosão.

Os requisitos

do sistema de ensaio para detecção de corrosão dependem do tipo e da

profundidade da corrosão para a qual a inspeção é realizada. Para

corrosão por corrosão uniforme e para grandes pites, os sistemas de

medição de espessura fornecem ótima detectabilidade. Para pequenos

pites e pequenas áreas de esfoliação ou ataque intergranular, os

requisitos de inspeção tornam-se semelhantes aos para falhas

subsuperficiais. Instrumentação e sondas com uma ampla seleção de

frequências de operação podem ser necessárias para cobrir a ampla gama

de tipos de materiais e espessuras. Equipamentos de análise de plano de

impedância operados por bateria podem ser usados para detecção de

corrosão e têm muitas vantagens para essas aplicações na maioria das

situações de campo.

5.17.2

Tipos de Corrosão.

Corrosão é uma deterioração de metais por ação

química. A corrosão ocorre quando um líquido condutor, como água com

íons, permite que os elétrons se movam de uma peça de metal para outra,

ou de um ponto para outro na mesma peça de metal. Se sal, ou outra

fonte de íons, for adicionado à água, a condutividade é aumentada e a

taxa de corrosão aumenta. Até mesmo a condensação do ar úmido pode

fornecer água suficiente para que a corrosão ocorra. As principais

defesas contra a corrosão em aeronaves são o isolamento de metais

diferentes uns dos outros e a proteção das superfícies metálicas contra

a umidade. Embora a corrosão possa ser classificada de várias maneiras,

para fins de detecção, cinco formas principais são consideradas: (1)

corrosão uniforme, (2) corrosão por pites, (3) ataque intergranular,

(4) esfoliação e (5) corrosão sob tensão.

NOTA:

Mais

explicações sobre a teoria da corrosão podem ser encontradas no

Capítulo 3 do NAVAIR 01-1A-509-1/TO 1-1-689-1/TM 1-1500-344-23-1.

5.17.2.1

Ataque Uniforme.

A corrosão por ataque uniforme é caracterizada por uma

redução geral na espessura do metal, na qual algumas áreas podem ser

corroídas mais rapidamente do que outras. Essa forma de corrosão é

facilmente detectável visualmente em superfícies expostas. A corrosão

de superfícies inacessíveis de estruturas metálicas finas é detectável

por correntes parasitas, se houver acesso ao lado não corroído. A

detecção desse tipo de corrosão torna-se então uma questão de medição

da espessura, com algumas variações esperadas devido a pequenas áreas

com aumento da corrosão ou à presença de materiais metálicos na

superfície mais distante.

5.17.2.2

Pontas.

Pequenas áreas localizadas de corrosão são denominadas pites.

As pites podem variar de tamanho pontual a áreas relativamente grandes.

A detecção e a medição de pites de corrosão devem levar em consideração

essas possíveis variações.

5.17.2.3

Ataque Intergranular.

Em alguns materiais, incluindo muitas ligas

estruturais de alumínio, a corrosão ocorre preferencialmente ao longo

dos contornos de grão. Embora pequenas quantidades de corrosão por

pites possam ser observadas na superfície, a extensão do dano não é

facilmente observável visualmente devido às pequenas penetrações

semelhantes a trincas. Este tipo de ataque é particularmente aplicável

a ligas de alumínio.

5.17.2.4

Esfoliação.

A corrosão por esfoliação inicia-se ao longo dos contornos

de grãos paralelos à superfície e propaga-se a partir desses locais de

iniciação. Os produtos da corrosão forçam o metal para cima, resultando

em bolhas e descamação do metal. Esta forma de corrosão é mais

prevalente em ligas de alumínio estruturais, como 7075-T6.

5.17.2.5

Trincas de Corrosão sob Tensão.

A combinação de uma tensão residual ou

de serviço aplicada constantemente e um ambiente corrosivo pode levar à

trinca por corrosão sob tensão em muitos metais de alta resistência. A

tensão residual pode resultar de tratamento térmico, usinagem,

conformação, ajustes por contração, soldagem e desengate de montagem.

Dependendo do tipo de metal e do ambiente corrosivo, a trinca por

corrosão sob tensão pode ou não estar associada a outras formas de

corrosão. Esta forma de corrosão é principalmente uma trinca e sua

detecção foi abordada em aplicações relacionadas à detecção de trincas

5.17.3

Seleção de Frequência.

A escolha da frequência depende do tipo de

corrosão a ser detectada e da espessura do material através do qual a

inspeção está sendo realizada. Frequências mais altas favorecem a

resolução de pequenas cavidades ou pequenas áreas de corrosão

intergranular ou esfoliação. Frequências mais baixas aumentam a

profundidade de penetração.

5.17.4

Seleção da Sonda.

A sonda deve corresponder à frequência com que a

inspeção de corrosão é realizada. Quando mais de um modelo de sonda é

operável na frequência de inspeção, a geometria da peça e da sonda são

os fatores determinantes na seleção da sonda. Para áreas de contato

estreitas, uma sonda de menor diâmetro pode ser vantajosa. Sondas de

maior diâmetro proporcionam uma média maior da espessura e proporcionam

uma sensibilidade um pouco melhor em áreas mais espessas.

5.17.5

Padrões de Referência para Corrosão.

Devido à ação única de cada tipo

de corrosão e seu efeito sobre a condutividade, os padrões de

referência devem ser fabricados com a mesma liga, têmpera e espessura

do material a ser inspecionado. Quando superfícies de contato estão

envolvidas na detecção de corrosão, o padrão deve ser construído para

simular a junta, incluindo calços não condutores para espessura de

folga, tinta e primer. Padrões para corrosão por pites também podem ser

usados para esfoliação e ataque intragranular. Os padrões também

devem ter aproximadamente a mesma geometria da peça.

5.17.6

Procedimento de Inspeção - Detecção de Corrosão.

A detecção de corrosão

com técnicas de correntes parasitas é aplicada a revestimentos de

aeronaves quando a corrosão pode ocorrer em superfícies internas

inacessíveis. A corrosão geralmente ocorre em áreas onde a umidade está

retida. Se for esperado um afinamento relativamente uniforme, a

detecção da corrosão pode ser simplesmente uma questão de medição da

espessura. Na maioria dos casos, a corrosão está confinada a áreas

menores e localizadas, de diâmetro relativamente pequeno. À medida que

a espessura do revestimento aumenta, a sensibilidade a pequenas áreas e

profundidades rasas de corrosão é reduzida.

5.17.7 Part Preparation. Prior to inspection, all foreign material

should be removed from the area to be inspected. Any roughness, sharp

edges, or protrusions that could damage the probe or cause errors in

readings should be removed by light sanding within the limits of the

applicable TO. The locations of all fasteners, edges, and changes in

structure on the far side of the inspection surface should be

established and marked with an approved removable marker to aid in the

interpretation of inspection results. Paint removal is not required if

it is relatively uniform and not loose or flaking. Because of the wide

variety of corrosion attack, inspection SHALL be performed in

accordance with the applicable TO

5.17.7

Preparação da Peça.

Antes da inspeção, todo material estranho deve ser

removido da área a ser inspecionada. Quaisquer rugosidades, arestas

vivas ou saliências que possam danificar a sonda ou causar erros nas

leituras devem ser removidas por lixamento leve, dentro dos limites da

TO aplicável. As localizações de todos os fixadores, arestas e

alterações na estrutura no lado mais distante da superfície de inspeção

devem ser estabelecidas e marcadas com um marcador removível aprovado

para auxiliar na interpretação dos resultados da inspeção. A remoção da

tinta não é necessária se ela estiver relativamente uniforme e não

estiver solta ou descascando. Devido à ampla variedade de ataques por

corrosão, a inspeção DEVE ser realizada de acordo com a Norma.

5.18 Medição de Condutividade em Campo.

Instrumentação de

correntes parasitas é utilizada para determinar a condutividade

elétrica em condições de produção e de campo. Os instrumentos de

correntes parasitas são calibrados de acordo com padrões de

condutividade conhecidos. Quando disponíveis, são utilizados

instrumentos projetados especificamente para medição de condutividade.

Esses instrumentos medem a condutividade diretamente em % IACS.

5.18.1

Condutividade de Ligas de Alumínio.

A medição da condutividade é

aplicada com mais frequência a ligas de alumínio. Essa aplicação

resulta do amplo uso de ligas de alumínio na indústria aeroespacial e

da ampla variação na condutividade elétrica e nas propriedades

mecânicas entre diferentes ligas e tratamentos térmicos. Para a maioria

das ligas de alumínio de uso comum, faixas de condutividade específicas

foram estabelecidas para cada liga e têmpera. As faixas de

condutividade para a maioria das ligas de alumínio comumente usadas em

aplicações estruturais de aeronaves estão listadas na Tabela 8-4, na

Seção 8. Esses valores representam um conjunto de valores obtidos

de vários fabricantes de fuselagens e agências governamentais. As

faixas incluem todos os valores obtidos para tratamentos térmicos

padrão, exceto os valores extremos obtidos de uma ou duas fontes que

estavam claramente fora das faixas de todas as outras listas. Se um

valor de condutividade medido para uma liga de alumínio e têmpera

estiver fora da faixa aplicável, suas propriedades mecânicas DEVEM ser

consideradas suspeitas. A medição dos valores de condutividade DEVE

estar de acordo com SAE-AMS-H-6088, ASTM E1004 ou outra norma adequada.

5.18.2

Efeitos do Tratamento Térmico na Condutividade do Alumínio.

Uma liga de

alumínio apresenta a maior condutividade e a menor resistência quando

está totalmente recozida. Após a têmpera a partir da temperatura de

tratamento térmico em solução, a resistência aumenta e a condutividade

diminui. Muitas ligas de alumínio permanecem instáveis por um período

considerável após o tratamento térmico em solução, mesmo quando

mantidas à temperatura ambiente durante esse período. Uma certa

migração de átomos ocorre para iniciar a formação de partículas

submicroscópicas. Esse processo, às vezes chamado de envelhecimento

natural, aumenta a resistência da liga, mas não tem efeito sobre a

condutividade ou apenas reduz ligeiramente seu valor. Algumas ligas de

alumínio permanecem instáveis por períodos tão longos após a têmpera

que nunca são utilizadas na condição de tratamento térmico em solução

(por exemplo, 7075). Se uma liga tratada termicamente em solução for

endurecida por precipitação por aquecimento a uma temperatura

relativamente baixa (geralmente 93-233 °C), os átomos de liga formam

pequenas partículas. Em um tamanho e distribuição de partículas

críticos, a resistência da liga de alumínio atinge o máximo. A

condutividade aumenta durante o endurecimento por precipitação ou o

processo de envelhecimento artificial. Se o envelhecimento for

prolongado além do ponto em que a resistência ideal é obtida, a

resistência diminuirá, mas a condutividade continuará a aumentar.

5.18.3

Discrepâncias no Tratamento Térmico de Ligas de Alumínio.

Variações em

relação às práticas de tratamento térmico especificadas podem resultar

em ligas de alumínio com resistências abaixo dos níveis exigidos. As

discrepâncias no tratamento térmico incluem alterações ou aplicação

incorreta dos seguintes processos:

- Temperatura do tratamento térmico da solução

- Tempo de tratamento térmico da solução

- Prática de têmpera Temperatura de envelhecimento

- Tempo de envelhecimento Temperatura e tempo de recozimento

- Aplicação de temperatura descontrolada

5.18.4 Aplicações da Medição de Condutividade.

NOTA:

As

Tabelas do Capítulo 4, Seção 8, fornecem valores e faixas de

condutividade para referência. No entanto, ao determinar a

operacionalidade de um componente ou estrutura de aeronave com base na

condutividade, a faixa de condutividade apropriada deve ser

identificada ou confirmada por engenharia especializada.

5.18.5

Separação de Ligas e Têmperas.

A medição de condutividade pode ser

usada para separar misturas de duas ou mais ligas e/ou têmperas. A

separação é possível quando a condutividade elétrica de cada grupo é

claramente diferente. O processo de separação pode ser realizado com um

instrumento calibrado em % IACS

5.18.6 Medição de Condutividade e Materiais Magnéticos.

O

uso de instrumentos de uso geral pode ser estendido à separação de

materiais magnéticos onde o produto da permeabilidade e da

condutividade de cada uma das ligas é claramente diferente. Medidores

de condutividade não medem a condutividade de materiais magnéticos.

5.18.7

Aplicação Típica.

Técnicas de correntes parasitas são utilizadas para

separar peças metálicas ou matérias-primas de geometria semelhante que

perderam a identificação da liga e/ou têmpera e se misturaram durante a

fabricação ou armazenamento. Tais procedimentos podem ser aplicados em

qualquer etapa do processamento, armazenamento ou serviço do material.

5.18.8

Controle do Tratamento Térmico.

A relação entre a condutividade

elétrica e as condições do tratamento térmico permitiu o uso de

técnicas de correntes parasitas para verificar a adequação do

tratamento térmico em ligas de alumínio. Nesta aplicação, medições de

condutividade por técnicas de correntes parasitas são utilizadas para

complementar uma quantidade mínima de ensaios de tração e/ou dureza. As

medições de condutividade por correntes parasitas são particularmente

valiosas para determinar a uniformidade do tratamento térmico de

estruturas de ligas de alumínio grandes e complexas quando amostras de

tração não estão disponíveis e a geometria da peça limita o acesso para

ensaios de dureza. A adequação do tratamento térmico de ligas de

alumínio é determinada pela conformidade do material com as faixas de

condutividade preestabelecidas. Este método de controle do tratamento

térmico tem sido amplamente aplicado a ligas de alumínio. Técnicas de

correntes parasitas são utilizadas para avaliar o tratamento térmico de

aços. Geralmente, instrumentação mais sofisticada é utilizada para

aços, mas instrumentos de uso geral podem ser utilizados para muitas

aplicações. Padrões de aceitação são geralmente utilizados para

inspeção de aços por correntes parasitas. A medição da condutividade é

aplicada em menor grau para o controle do tratamento térmico de ligas

de cobre e magnésio. Técnicas de correntes parasitas podem ser

utilizadas para o controle do tratamento térmico em qualquer sistema de

ligas onde faixas de condutividade ou valores de permeabilidade

consistentes, porém diferentes, ocorrem com as diversas condições de

tratamento térmico. A medição da condutividade não foi estabelecida

como um método para determinar a resposta ao tratamento térmico em

ligas de titânio. As diferenças na condutividade entre as diversas

condições de tratamento térmico para a maioria das ligas de titânio são

insuficientes para permitir a determinação da têmpera.

5.18.9

Determinação de Danos por Calor e Fogo.

Uma aplicação comum da medição

de condutividade em aplicações de campo é a determinação de danos por

calor e/ou fogo em estruturas de aeronaves. Devido ao amplo uso de

ligas de alumínio em estruturas de aeronaves e sua sensibilidade a

perdas de propriedades mecânicas em temperaturas relativamente baixas,

a maior experiência e dados foram gerados para esses materiais. Danos

por calor e fogo em outros metais podem ser detectados se as

temperaturas se tornarem altas o suficiente para afetar a

condutividade, a permeabilidade e as propriedades mecânicas. Danos são

detectados em ligas de alumínio como mudanças na condutividade em

relação à faixa especificada para a liga e têmpera que estão sendo

inspecionadas. Danos por calor e fogo geralmente variam em uma peça

devido à aplicação não uniforme de calor. A aplicação não uniforme de

calor, por sua vez, resulta em variações na condutividade elétrica. A

menos que a temperatura e o tempo de aplicação de calor sejam

conhecidos, ou que o teste seja realizado em várias peças com o mesmo

histórico de aplicação de calor, valores quantitativos de propriedades

mecânicas não podem ser estabelecidos a partir dos valores de

condutividade elétrica. Os testes de dureza e a medição de

condutividade fornecem uma boa indicação de danos por calor e fogo.

Ambos os métodos de teste devem ser realizados para se ter uma ideia da

quantidade de dano.

5.18.10

Medição de Condutividade.

Para determinar a condutividade diretamente,

estão disponíveis instrumentos de correntes parasitas que fornecem um

valor de condutividade em % IACS. Instrumentos de medição de % IACS

geralmente requerem apenas dois padrões de condutividade conhecidos

para calibração. Se não houver equipamento de medição direta de

condutividade, equipamentos de correntes parasitas de uso geral podem

ser adaptados para medir a condutividade. O uso de equipamentos de uso

geral requer um número maior de padrões para estabelecer uma curva de

calibração. O número de padrões necessários para uma aplicação de

medição de condutividade é determinado pela faixa de condutividade a

ser coberta e pela precisão necessária. Equipamentos de uso geral

também podem ser usados em uma função passa-não-passa para separar

metais acima e abaixo de um valor de condutividade especificado. Um

padrão representando a condutividade mínima aceitável ou não permitida

deve estar disponível.

5.18.11 Equipment for Magnetic Materials. Impedance plane analysis instruments can be used to measure the conduc

tivity of ferromagnetic materials because the permeability and conductivity can be separated in phase. The combination of

conductivity and permeability, in many cases, can be related to variations in alloy, temper, and strength. General purpose me

ter type instruments can then be used to separate or grade various levels of properties. The number of standards required

depends on the number of categories of materials to be established.

5.18.11

Equipamentos para Materiais Magnéticos.

Instrumentos de análise de

plano de impedância podem ser usados para medir a condutividade de

materiais ferromagnéticos porque a permeabilidade e a condutividade

podem ser separadas em fase. A combinação de condutividade e

permeabilidade, em muitos casos, pode estar relacionada a variações na

liga, têmpera e resistência. Instrumentos de medição de uso geral podem

ser usados para separar ou classificar vários níveis de propriedades.

O número de padrões necessários depende do número de categorias de

materiais a serem estabelecidas.

5.19 Efeitos das Variações nas Propriedades dos Materiais.

5.19.1

Condutividade.

Variações na condutividade podem ocorrer em metais como

resultado de tratamento térmico inadequado ou como resultado da

exposição a temperaturas excessivas durante o serviço e o trabalho a

frio. Essas são as condições para as quais a inspeção por correntes

parasitas geralmente é realizada. Variações na condutividade podem

advir de outras fontes. A separação de elementos durante a

solidificação de metais pode levar a diferenças localizadas ou

uniformes na condutividade. Por exemplo, pode haver uma variação na

condutividade com o aumento da profundidade abaixo da superfície da

peça, particularmente em seções mais pesadas que não foram trabalhadas

extensivamente. Pequenas diferenças no tempo de tratamento térmico,

temperatura ou taxas de têmpera impostas por limitações nas instalações

de tratamento térmico ou mudanças na configuração da peça também levam

a variações na condutividade de uma peça. O trabalho a frio localizado

de metais, quando não seguido por tratamento térmico para aliviar a

tensão residual, pode reduzir a condutividade elétrica. Muitas das

variações são consideradas normais ao processamento das peças e a

condutividade está dentro da faixa aceitável para a especificação e

têmpera da liga. Condutividade fora da faixa especificada para uma dada

liga e têmpera deve ser considerada inaceitável e investigações

adicionais devem ser realizadas usando técnicas de teste de dureza.

5.19.2

Efeitos de Borda.

Se o campo eletromagnético da sonda for afetado pela

geometria da borda da peça, ocorrerá um erro na medição da

condutividade. A sonda deve ser localizada a vários diâmetros de sonda

de distância da borda ou limite de transição mais próximo.

5.19.3

Curvatura. Efeitos de lift-off causados pelo encaixe da sonda na

superfície curva causarão um erro na medição da condutividade. Em

superfícies curvas, a menor sonda prática deve ser usada para minimizar

os efeitos de elevação.

5.19.4

Materiais Revestidos.

O revestimento afetará a condutividade medida do

metal base. O grau em que o revestimento afetará o valor obtido depende

da condutividade do revestimento, da espessura do revestimento e da

frequência de operação. As aplicações atuais geralmente se limitam a

ligas de alumínio "Alclad" na faixa de 0,050 a 0,080 polegadas de

espessura, utilizando medidores de condutividade com frequências de

operação de 60 kHz. Faixas especiais de condutividade são necessárias

para ligas de alumínio revestidas. As espessuras do revestimento, que

geralmente são baseadas em uma porcentagem da espessura total, podem

variar ligeiramente devido às tolerâncias normais. A 60 kHz, as

leituras de condutividade de ligas de alumínio com espessura inferior a

0,050 polegadas são afetadas tanto pela espessura do revestimento

quanto pela espessura da peça. Os testes de correntes parasitas de

sistemas complexos de revestimento ainda estão, em sua maior parte, em

fase experimental.

5.19.5

Permeabilidade Magnética.

A medição direta da condutividade elétrica

por medidor é aplicável a materiais não magnéticos com permeabilidade

magnética relativa de um ou quase um. Se a permeabilidade magnética

exceder um, ocorrerá um desequilíbrio de ponte no sistema do medidor,

que não pode ser separado da medição de condutividade, e leituras

errôneas serão obtidas. Por esse motivo, a condutividade de aços,

níquel e outros materiais magnéticos não pode ser determinada com

medidores convencionais de condutividade por correntes parasitas.

Alguns aços inoxidáveis (por exemplo, série 300) são essencialmente

não magnéticos na condição recozida, mas pequenas quantidades de

trabalho a frio ou exposição a temperaturas extremamente baixas podem

causar a transformação em uma estrutura magnética. Equipamentos de

análise de plano de impedância podem separar facilmente a

permeabilidade magnética da condutividade, permitindo uma medição

precisa da condutividade de materiais ferromagnéticos.

5.19.6

Geometria.

Qualquer alteração na configuração da peça que afete a

distribuição ou penetração de correntes parasitas resultará em leituras

errôneas de condutividade elétrica. As seguintes fontes de erro estão

incluídas nessas categorias:

- Proximidade de bordas parciais ou estrutura adjacente

- Espessura do metal menor que a profundidade efetiva de penetração no metal

- Curvatura excessiva da superfície da peça

5.19.7

Espessura do Metal.

Se a espessura do metal for menor que a penetração

efetiva das correntes parasitas, a condutividade medida será diferente

do valor real. Observe que a profundidade de penetração efetiva é

aproximadamente três vezes a profundidade padrão de penetração. Com

equipamentos de medição, é importante determinar a frequência de

operação do instrumento. A frequência de operação não deve exceder a

profundidade de penetração efetiva do material a ser testado.

Equipamentos de análise de plano de impedância possuem uma ampla faixa

de frequências de operação, e a frequência pode ser ajustada para

limitar a penetração a menos que a profundidade efetiva. A profundidade

padrão pode ser determinada usando a equação do Seção 8, Parágrafo 8.7. Réguas

de cálculo especiais estão disponíveis para calcular a profundidade de

penetração. A profundidade efetiva é aproximadamente três vezes maior

que a profundidade padrão calculada por esta equação. A espessura do

material deve ser maior que a profundidade efetiva, caso contrário,

ocorrerão erros na medição da condutividade.

5.20 Efeitos das Variações nas Condições de Ensaio.

5.20.1

Frequência.

Como a frequência afeta a distribuição das correntes

parasitas dentro da peça de teste, ela afeta a espessura mínima que

pode ser medida sem ajustes especiais. Frequências mais altas permitem

a medição de metais mais finos sem compensação de espessura. Selecione

uma frequência tal que a profundidade efetiva de penetração (2,6 )

esteja contida no metal sendo testado para uma medição de condutividade

razoavelmente precisa. No entanto, as frequências mais altas são mais

fortemente afetadas por variações localizadas na condutividade ou por

revestimentos e revestimentos condutores em metais. Frequências

excessivamente altas NÃO DEVEM ser usadas para medições de

condutividade.

5.20.2

Sondas para Medições de Condutividade.

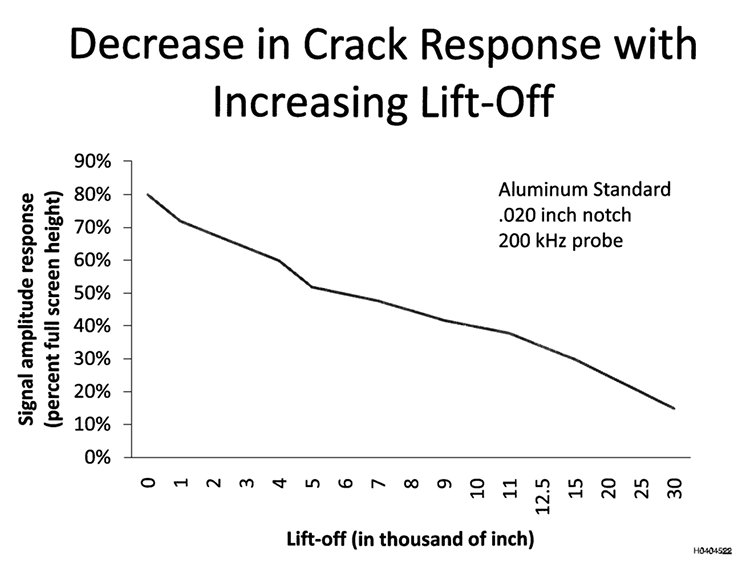

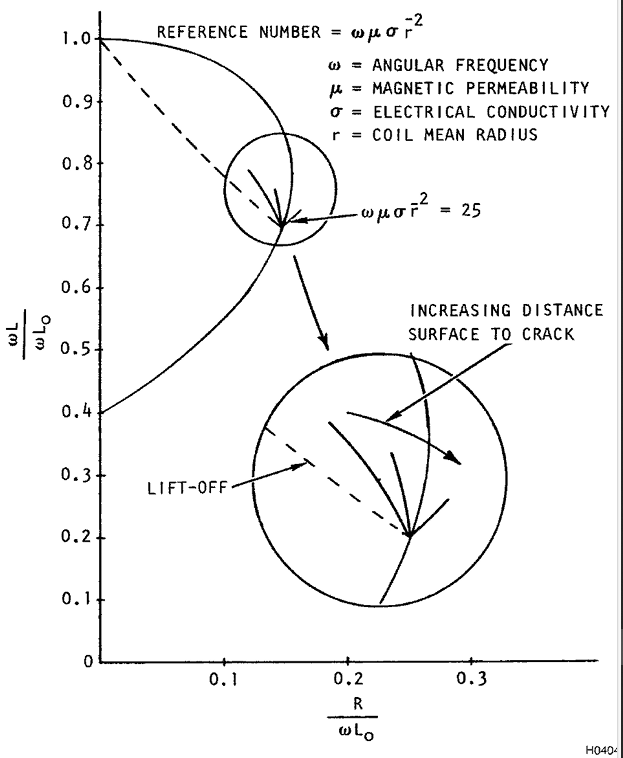

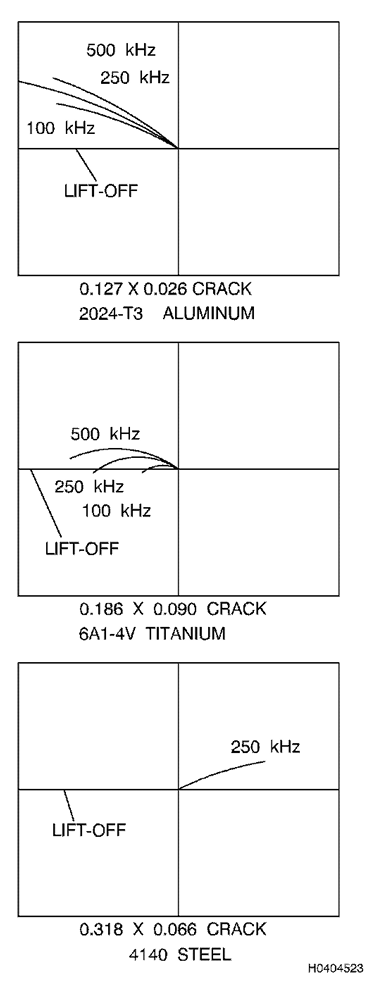

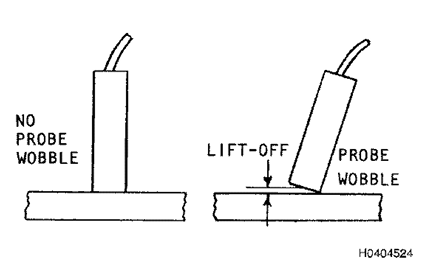

Com instrumentos projetados para